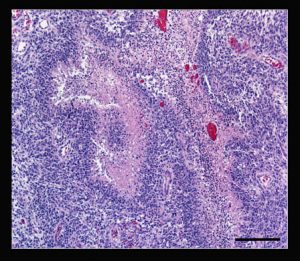

Photo — Brain scans from a 7-year-old female Boston terrier, Virginia Tech

From Oh My Dog!

The rare form of brain cancer that killed John McCain and Ted Kennedy has also been a death sentence for many dogs, but researchers are seeing at least a little hope for canines in an experimental treatment being studied at Virginia Tech.

Researchers at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech are enrolling dogs with glioblastoma into a clinical trial to test the experimental drug that is injected directly into the tumors.

They say the results are so promising that the National Institutes of Health is now helping fund the trial, hoping it could eventually lead to a breakthrough in humans.

McCain succumbed to the cancer Aug. 25, exactly nine years to the day after Kennedy, his former colleague in the Senate, did.

Dogs and humans are the only species in which primary brain tumors are common. In dogs, a glioma accounts for about 35% of all spontaneous primary brain tumors. The prognosis for both dogs and humans diagnosed with the cancer is poor.

In the Virginia Tech clinical trial, researchers are testing the safety and effectiveness of molecularly targeted cytotoxins, which are chemotherapeutic drugs — a treatment developed at the Thomas K. Hearn Brain Tumor Research Center at the Wake Forest School of Medicine.

The drugs are designed to affect only cancerous cells, and not normal brain tissue. Using specialized catheters the cytotoxins are infused into the tumor over a several hour period. The drug treatment is monitored continuously with MRI to allow the neurosurgeon to precisely track the drug delivery.

CBS News reported on the trials recently and interviewed the owners of one of the study’s participants — a 10-year-old Portuguese water dog named Emily.

Laura Kamienski said she was devastated when her dog was diagnosed earlier this year, and was willing to try any experimental treatment available.

It has been six weeks since Emily’s first treatment and Kamienski said Emily hasn’t had a seizure. MRI scans show Emily’s tumors are shrinking.

“She’s herself,” she said.

“We watch the entire treatment on MRI,” Dr. John Rossmeisl, professor neurology and neurosurgery at Virginia Tech, told CBS News. “So we can watch the drug cover the tumor. And so we know we’ve achieved the treatment goals of actually targeting all the cancer cells.”

“The black spot means the tumor is dying. That’s what we want to see,” Rossmeisl said. “The only way this could have been better if it was totally gone. This is really good news.”

“It’s not a cure, Kamienski said. “I knew that going in. This is the best hope — to give her more time.”